Written by Ron Barbish, owner of watermanatwork.com, reflecting his personal views based on years of observation and direct experience on the Columbia River.

The decline of fishing in a natural wonderland like the Columbia River Gorge is a sad story to tell. It’s not the kind of story I want to be writing about a place where I live. You could see it coming for years, but hopes that nature would bounce back have been crushed by the reality of a rapidly changing local environment, an unstable political situation and the mismanagement of natural resources.

The most visible and most widely reported decline of fish populations on the Columbia River are the salmon and steelhead. These fish live in the Pacific Ocean and migrate up the Columbia River to spawn in the Columbia’s tributaries. Due to a number of environmental and human encroachment issues, the numbers of salmon and steelhead returning to the Columbia River to spawn have been decreasing rapidly. As it stands today, there are multiple, consecutive years of stunningly declining salmon and steelhead runs. There may be a year or two when the salmon run is “50% above last season”, but “last season” was part of a multi year, 25% less fish per year decline. One step forward after five steps back. The decline of such an important commercial and symbolic part of the Pacific Northwest has focused on the many problems of this unique part of the United States.

The main problem for the salmon is mainly human encroachment. More people means more environmental decline; it’s the same story every time. The Columbia River Gorge is a spectacular natural wonder, but nearly all of it has been altered and controlled by humans.

Large dams have changed the Columbia River to accommodate the increasing population’s endless demands for water and electricity. Large dams on large rivers have a large impact on the environment, changing it dramatically in most places. Many of these changes have effects that do not appear for decades.

The construction of the dams changed the river into, more or less, a series of large lakes or “pools”. The dams also blocked the upstream migration of salmon and steelhead. The dams cause the Columbia River water to be warmer which affects the river ecosystem. Fish ladders and passageways through the dams allowed some of the fish to get through, but a large dam makes for a tough obstacle for spawning fish. The fish passageways through the dams also allow growing numbers of non-native American Shad that could crowd out the native salmon and steelhead. Native Americans who lived near the river and depend on the salmon for sustenance were displaced.

The dams provide a good deal of electricity and prevent flooding. Farms and orchards line the Columbia River, a prime agricultural region. As the population of the Pacific Northwest continues to grow at an expanding pace, agriculture, growing cities and the natural environment compete for what may turn out to be the most valuable resource of all; water. The entire area depends on water stored behind Columbia River dams.

If the spawning salmon and steelhead make it past a couple huge Columbia River dams, the river tributaries where the fish are headed to spawn may be impassible to low water levels or dried up completely. Snow melts in the mountains, the small streams run into bigger streams that eventually empty into the Columbia River. This web of mountain streams is the salmon and steelhead spawning ground. If the streams are dry, the fish can’t spawn and they die trying. Between the mountain snow and the Columbia River there is a good deal of agriculture and an increasing population that uses more of the snowmelt water, leaving less for the salmon streams.

An option favored by some is remove the dams on the Columbia River. Sea lions, normally found in the coastal waters of the Pacific Ocean, have made their way up the Columbia River, following the salmon who are easy prey when blocked from swimming upstream by huge dams. Columbia River dams regulate and store precious water in a drought stricken west and they provide hydroelectric energy to a growing Pacific Northwest population. Breaching dams on the Columbia River at this point may do more harm than good, so removal of Columbia River dams seems unlikely. There is growing pressure to remove dams on the Lower Snake River in Idaho that feeds into the Columbia and blocks salmon migration. These dams provide a modest amount of electricity and could possibly be replaced by renewable energy sources.

Commercial and tribal fishing are probably the next largest factor, after environmental changes, the salmon population is in rapid decline. It is likely nobody really knows how many salmon are caught by commercial fishing boats around the mouth of the Columbia River. Tribal fishermen still use gill nets to catch the migrating salmon, steelhead and anything else that swims by. Gill nets are very effective for catching fish and have been banned just about everywhere in the world. Gill netting has a proven track record of decimating fish populations, it would be difficult to believe that tribal gill netting has not had an effect on the diminishing Columbia River salmon population.

Most of the Columbia River, the dams and a significant chunk of the riverside property is owned by the government and managed by several state and federal agencies. Technically, this land is owned by the people of the United States, but we all know that’s not really the case. The states of Oregon, Washington and Idaho also have a hand in managing and regulating natural resources in the area. As Americans learn more about what’s really going on with the government, there’s a good deal of negative feelings towards these federal and state wildlife agencies as it becomes more apparent that the primary focus of the government is quick money and not positive natural resource management.

Mistrust of the government agencies managing of Pacific Northwest public land is high and with good reason. Almost everyone has reason to mistrust these absentee government agencies, I have one as well. One morning, salmon fishing at the White Salmon river mouth a short distance from my home, a Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife(WDFW) patrol boat motored through a pack of forty boats over to my kayak twenty feet off the bank getting rigged up for fishing. They gave me the whole id check, boat safety check and checked my fishing license. I did not have my salmon catch card, which is a document required by the state to record the salmon you catch, in the kayak.

Everything on a kayak that is fishing for salmon on the Columbia River is wet, so I would record the fish I caught when I got back to my truck and dried off. I was given a $150 citation for not having the paperwork on the kayak. I offered to paddle over to my truck, fifty yards away, and get the paperwork, but the WDFW officer refused the offer and told me he suspected me of being a poacher. Of course this was a totally false accusation with no evidence or reason to back it up. It was a cowardly way to get money out a totally innocent person.

In the past, I had called the WDFW to report poachers, including this exact fishing spot, and they weren’t interested. I also came across two poachers who had just shot a deer out of season. I was unarmed, the poachers were not. A dangerous situation for anyone, but neither WDFW or the county sheriff were interested. In another incident, a poacher had strung a gill net across the mouth of the Klickitat River. The Klickitat River is neither remote nor hidden from view but it took a few days to get the WDFW to check it out. Judging by what I’ve experienced, the WDFW is not interested in preventing poaching, just profiting from it.

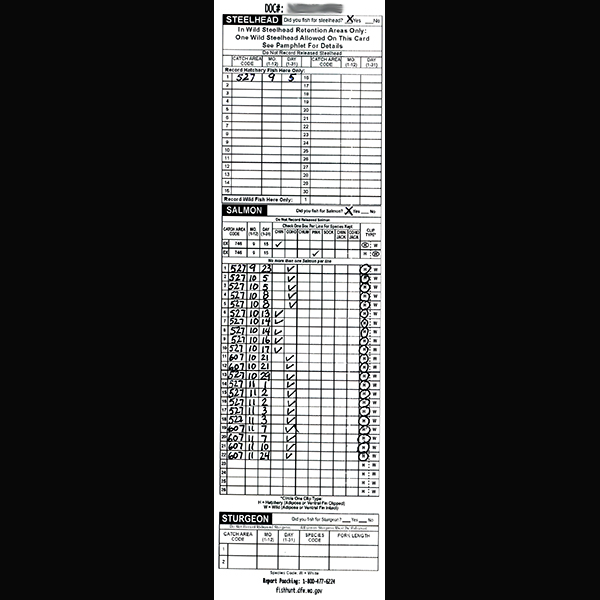

To be clear, I have accurately filled out and returned a fishing catch card every year I have purchased a Washington fishing license. I follow all fishing laws and regulations. I encourage catch and release in the watermanatwork.com blog and kayak fishing videos. The catch card in the photo above is from 2014. Steelhead retention is history and you would have to do a lot of salmon fishing to catch over twenty salmon in a season the way things currently stand.

Perhaps the steelhead and salmon are going to wind up on the endangered species list along with the Columbia River sturgeon, but at least there are smallmouth bass. Vilified in the past by government agencies for eating young salmon, the humble smallmouth bass is looking like the Columbia River sportfisherman’s best bet.

I always have said if you can’t catch smallmouth bass on the Columbia River, then there aren’t any fish around. Several years ago I said the Columbia River and some of its tributaries, especially the John Day River, may have been one of the best places to fish for smallmouth bass in the entire country. I don’t think that’s the case any longer. We’ve caught some big smallmouth bass on the Columbia and used to go out fishing thinking there was a realistic chance of getting close to a record size fish.

I hope the big ones are still there because it has been a long time since I have caught a big smallmouth bass. In recent years the smallmouth bass seem to have gotten fewer and generally a lot smaller. It could be said I’ve lost the touch for catching smallmouth bass, but fishing in the same spots at the same time with the same fishing methods, there are definitely less and smaller smallmouth bass.

Like any other large river controlled by dams, the water levels on the Columbia River go up and down on a regular basis. This usually slows down the fishing for a few days, especially if the water is low in the heat of the increasingly hot PacNW summers. Dwindling water supplies are an increasing issue in the parched American west but the real problem with the smallmouth bass, perhaps the salmon and the Columbia River in general, may be invasive aquatic vegetation.

The waters of the Columbia River are becoming increasingly infested with aquatic vegetation. Water on the Columbia River, backwaters and boat harbors up to twenty feet deep is choked with thick weeds. When the water warms up and the days get longer in the spring, this vegetation starts to grow at an amazing rate. Covering the rocks in the river, which is mostly rocky, is a thick, bright green algae, which is quite slimy and sticks to everything. The algae sticks to a boat or trailer and rides to a new home. Especially troublesome is the invasive plant Eurasian Milfoil. The milfoil expands by plant segments breaking off and taking root elsewhere. Invasive milfoil displaces native plants and animals and must be poisoned to eradicate it. To do that on such a large scale may not be possible.

Why do these aquatic plants on the Columbia River grow so quickly and spread so rapidly? Even though the Pacific Northwest winters are gray, cold and long, the summer days are long with abundant sun. The Columbia River is lined with agriculture that depend on the river water for nearly it’s entire length. These farms, orchards and ranches provide fruit, vegetables and livestock for millions of people.

They also use a lot of chemicals to do so, including pesticides, herbicides and fertilizer. The same fertilizers used to grow melons, onions, pears and apples works its way down the short distance to the Columbia River, where it seems likely to have enhanced the growth of invasive aquatic species as well as the native vegetation.

The current river environment seems to have had an adverse effect on the smallmouth bass and their favorite food, crayfish. People will say nature works in up and down “cycles”, which may be true, but there are also major one way trends. Just as the salmon, steelhead and possibly smallmouth bass are on their way out, thick mats of milfoil and slimy algae are on the way in.

In addition to all these things, there can be little doubt that, man made or otherwise, the climate of the Pacific Northwest and the rest of the world appears to be changing to a pattern of extreme and unusual weather. For the Pacific Northwest, so far at least, that has meant drought and extreme heat. That means more and larger wildfires. There’s erosion after forest fires and the runoff fills up the salmon spawning creeks.

One of the great things about this part of the Pacific Northwest is that it’s one of the few places you can camp without being in a campground and go fishing wherever there wasn’t a “No Trespassing” sign. In these rural areas, hopping in the camper and camping by the river was a cool and affordable way to spend a hot summer weekend without driving a long ways. The outdoors is a way of life around here.

As a kayak fisherman, there are very few places you can camp with your kayak at the waters edge and the Columbia River was one of those places.

After all, this is the same place Lewis and Clark paddled their canoes down the Columbia River. It looked a lot different back then, but you’re paddling the same water they did. Following Lewis & Clark’s trip down the Columbia is a goal for kayakers and canoeists. They have to make a significant portage to get around the large Columbia River dams. This is one of the places to camp.

Slowly but surely, these camping and river access spots are being restricted or closed. Camping at the spot in the photos above is no longer allowed. These are remote spots used mostly by local residents, travelers and fishermen. Aside from fishing, there is nothing at these spots to keep anyone for more than a day or two. Other spots popular with summer travelers, especially RV type people have been closed as well. There are an increasing number of Americans who, by choice or circumstance, spend their lives on the road. Most come and go but more and more people will stay as long as they are able.

I asked one of the government employees who was checking on people camping for more than seven days in a thirty day period, why the areas were closing, she told me it was “too much to manage”. The government agencies tasked with managing public resources are saying they can’t, or won’t, do the job they are being paid by taxpayers to do. It’s easier for them to restrict access by the public to public land.

These public lands were closed due to the COVID pandemic and never reopened. Closed public land needs nearly the same management as open public land and the closed land makes no money for the government. Perhaps these areas are only closed temporarily and will reopen with new government permits required.

Columbia River fishery mismanagement, allotment of precious Columbia River water, management of, and access to, large swathes of public land have added to an already tense situation in this part of the country. The states of Washington and Oregon are literally divided down the middle as far as politics go. Portland, OR, the poster city for what you don’t want to happen in your city, is about an hour away. This is a beautiful natural area that is increasingly a place of diminished returns and a cloudy future.

Salmon fishing has become mob scene of fishermen desperate to catch one salmon. Crowded parking lots and fishing that resembles small scale naval warfare is the norm with diminished salmon runs. Vehicles parked at boat launches and outdoor areas are not as safe as they used to be.

In the summer, when it’s not too windy, the river is choked with aquatic vegetation and algae. The smallmouth bass get smaller every year and now you have to drive an hour each way for a couple hours of fishing and a few small fish.

As an avid lifelong fisherman, I never thought I would see the day when it wasn’t worth it to go fishing. For me and the Columbia River, that day has come. The cost of the simple act of fishing has keeps rising and there will never be another day of fishing here better than one I’ve already had.

I’m sorry for the young kids who will never get a chance to experience real fishing and I’m sorry for the retired guys who spend their golden years staying alive for another day on the water. Fishing is one of those things that stays with you your entire life, gets you more in touch with nature and promotes patience and optimism. The best day of fishing is supposed to be the next day of fishing.

The road ahead in the United States looks to be a rocky one and the future seems much more uncertain than ever. Spending millions of taxpayer dollars to operate salmon hatcheries, boat the young salmon down the Columbia to the Pacific Ocean where they wind up in the freezer of a commercial fishing boat or caught in a tribal gill net does not appear to be working. Nearly every problem can be solved with common sense and/or logic, but federal and state governments appear to have management problems across the board so there is little hope things will go the right way with the complex environment of the Columbia River.

And you can’t forget about your problems by going fishing.

Thanks for writing this, fishing inside the mouth of the White Salmon river was my favorite place to fish, I don’t think there was another place like it, trolling at night catching steelhead. From the Seattle area I would drive down every weekend and every other Tuesday night. Miss that place.

https://m.youtube.com/watch?v=3S90L3ITKyU